Emerging Therapies for COVID-19: Convalescent Plasma

Open article published on MedShr: 14th October 2020

Last updated: 14th October 2020

Every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this article is accurate and current at time of publication, but if you notice an error please contact covid@medshr.net and we will aim to address this. Please find MedShr’s full terms of service here.

Current Situation:

Position from the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel (NIH), updated 9th October 2020:

“There are insufficient data for the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel (the Panel) to recommend either for or against the use of COVID-19 convalescent plasma for the treatment of COVID-19.” [1]

US Food and Drug Administration:

“On August 23, 2020, FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for COVID-19 convalescent plasma for the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. However, adequate and well-controlled randomized trials remain necessary for a definitive demonstration of COVID-19 convalescent plasma efficacy and to determine the optimal product attributes and appropriate patient populations for its use.” [2]

Prior to this a national Expanded Access Program (EAP) was run by the Mayo Clinic [3,4]. A useful summary of what the current FDA guidance means is provided by the American College of Cardiology [5], but importantly this EUA does not equate to a licence for convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19. At time of writing, no country in the world has licenced convalescent plasma for the treatment of COVID-19. [6]

In the UK, NHS Blood and Transplant are collecting plasma from patients who are anti-SARS-CoV-2 positive for treatment in two trials: REMAP-CAP (convalescent plasma given to patients in intensive care within 48 hours of diagnosis), and RECOVERY (convalescent plasma given to hospitalised patients not in intensive care). [7]

Several clinical trials are ongoing:

Current Registered Randomised Clinical Trials on ClinicalTrials.gov [8]

Summary of Key Scientific Papers by the National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project [9]

Background:

Terminology:

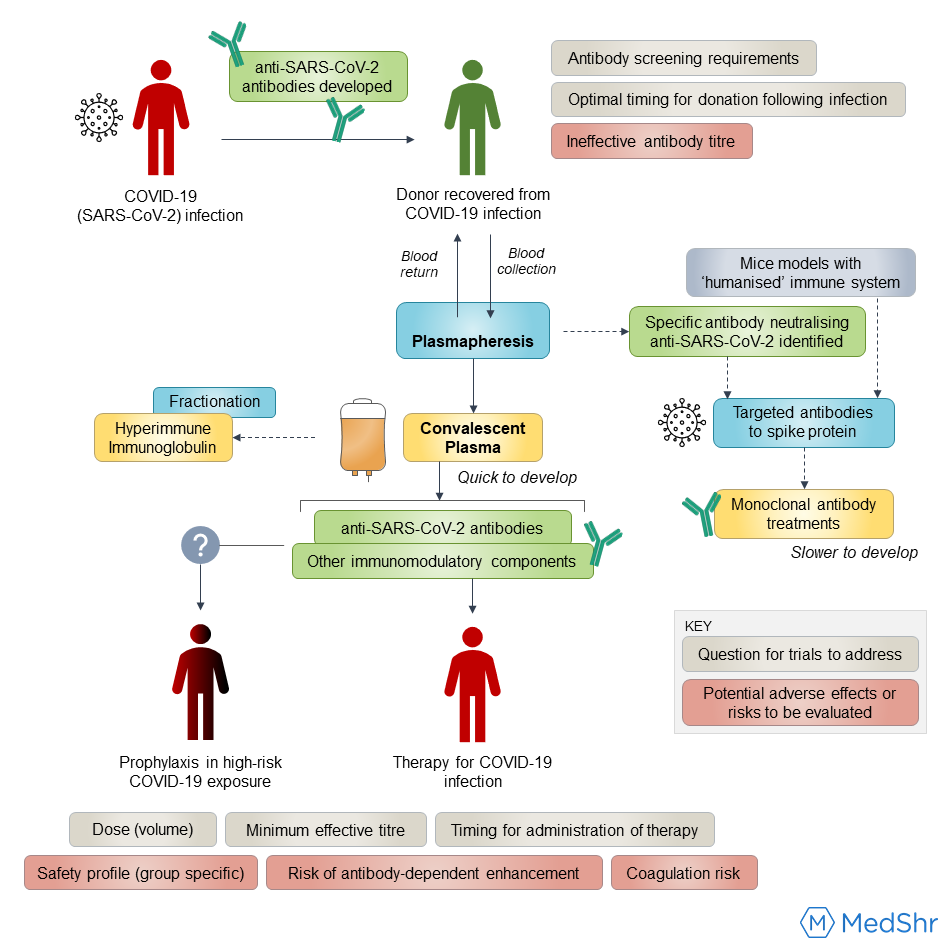

Convalescent Plasma: a form of ‘passive immunity’ whereby human plasma is collected from patients who have recovered from a disease, in this situation SARS-CoV-2, where the expected effect is anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (and other plasma components) may help neutralise the viraemia and improve clinical outcomes for patients infected with COVID-19 [10]. Convalescent plasma includes other plasma components like coagulation factors,[11] and both direct and indirect mechanisms for how convalescent plasma may help alter the clinical course have been proposed. [12,13]

Hyperimmune Immunoglobulin: a standardised antibody dose prepared by fractionation of human convalescent plasma, which removes other plasma components such as coagulation factors and other antibodies (e.g. IgM) [6,10 ,14,]

Monoclonal antibodies: unlike the polyclonal antibodies present in convalescent plasma, monoclonal therapies use an antibody gene in a single B cell to make identical clones of a single desired antibody; this antibody will have been identified to have a neutralising effect on a region of the spike protein on SARS-CoV-2. [15,16] Such therapies are in development, and these ‘antibody cocktails’ hit news headlines recently after President Trump received an investigational new drug made by Regeneron whilst being treated for COVID-19. [17]

Previous Use:

Attempting to generate passive immunity using convalescent plasma is an approach that has been employed in medicine for over a century for conditions such as diphtheria, polio, mumps, measles and pneumococcal pneumonia. [9,14,18] This approach was also used during the 1918 influenza pandemic, and more recently in infectious disease epidemics including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS, 2002-04), influenza A (H1N1, 2009), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS, 2012) and Ebola virus disease. [10,14,18,19]

There are proven benefits for virus-specific immunoglobulin preparations in conditions such as hepatitis B and rabies (licenced for post-exposure prophylaxis in both conditions), but only one randomised controlled trial has shown benefit for convalescent plasma. [1,5,19] A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis suggested convalescent plasma “may reduce mortality and appears safe” for use in severe acute respiratory infections (SARS), but recommended further well powered randomised controlled trials (RCTs). [20]

Current Research:

Analysis and Up-to-Date Articles

A comprehensive summary and analysis of the current literature evaluating the effectiveness of convalescent plasma can be found at the National Institutes of Health - COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines.

A database search of registered randomised clinical trials investigating plasma therapy is accessible at ClinicalTrials.gov

And finally, a living systematic review and meta-analysis by Piechotta et. al can be found in the Cochrane Library.

Research Challenges

A common challenge to evaluating the available literature relates to the lack of well-controlled, adequately powered, randomised clinical trials. [1] Observational data can introduce potential confounding or complexities to data interpretation due to the lack of a control treatment arm [6,21,22]:

Naturally, patients may also be receiving several other therapies and interventions, thus it is difficult to determine the benefit, if any, a convalescent plasma intervention had compared to the other interventions.

The timing of administration typically varies in the available studies, therefore it is not yet clear when optimal time of administration of plasma therapy may be.

Volumes of convalescent plasma administered vary widely.

Antibody titres in the convalescent plasma are highly variable.

Next Steps and Challenges:

Current and historical data on the safety of convalescent plasma transfusion generally supports it is equivalent in risk to transfusion of other blood products. [12,23] The multi-centre Expanded Access Programme run by the Mayo Clinic in the US has reported on the adverse effects in 20,000 hospitalised patients treated with convalescent plasma between April and June 2020 and supports this stance. [4]

However, several questions must still be answered by well-designed and adequately powered randomised clinical trials, including:

Donor selection: what criteria define the optimal donor, e.g. severity of infection, and how long after COVID-19 infection do antibody titres remain at an acceptable level for use in convalescent plasma treatment? [12,24]

Patient Selection: current research suggests earlier administration of convalescent plasma in the disease course improves outcome [4], but this is yet to be confirmed in RCTs. When do hospitalised patients develop similar antibody titres to the transfused plasma, thus decreasing the potential efficacy of convalescent plasma? [1]

What is the minimum-effective antibody titre and required plasma volume of infusion? [1,21]

If proven to be an effective treatment, how can healthcare systems and governments plan to ensure a steady supply of convalescent plasma therapy? [21]

What are the risks and benefits of convalescent plasma therapy in specific circumstances. e.g. in paediatric or pregnant patients?

Could plasma therapy be used as a prophylactic treatment in individuals not yet infected but who have had a high risk exposure (RCTs in progress) [8,25]

Could coagulation factors transferred in convalescent plasma influence the already pro-thrombotic state seen in COVID-19 [14,23]

Is there a risk of antibody‐dependent enhancement of infection in COVID-19? [14,15,23]

Challenges for Implementation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC’s):

Issues surrounding the availability of blood products for transfusion globally (the ‘transfusion deficit’) predate the current COVID-19 pandemic, but highlight the challenges LMICs may face in implementing research programmes and subsequent potential treatment with convalescent plasma. [24]

For example, convalescent plasma can be obtained in larger quantities and at much more frequent intervals than whole blood donations (weekly vs 2-3 monthly) but a limited availability of facilities for plasmapheresis makes this approach challenging in low-resource settings. [13,26]

Bloch et al. [26] have discussed these challenges and potential solutions for more widespread availability of convalescent plasma therapy.

Useful web resources:

NHS Blood and Transplant Plasma Programme

JAMA Patient Page: Convalescent Plasma

National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project

FDA Fact Sheet: Emergency use authorisation for COVID-19 convalescent plasma

COVID-19 Research: Resources

There has been a vast amount of research published since the beginning of the pandemic. In the past week (5th October to 11th October 2020) there were 1493 new research articles listed on LitCovid, with the peak number of papers published in one week sitting at 4286 papers between 24th August and 30th August 2020.

Trying to navigate this expanding catalogue of information to remain up-to-date with the latest developments is challenging, especially alongside clinical practice.

Below is a list of useful bodies and organisations who are making great efforts to categorise, evaluate and summarise this research to ensure optimal patient care globally; we hope you find this article useful and if you discover any other great resources please feel free to share these in the comments section below.

LitCovid: “LitCovid is a curated literature hub for tracking up-to-date scientific information about the 2019 novel Coronavirus... articles are updated daily and are further categorized by different research topics and geographic locations for improved access.”

National Institutes for Health: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines

Continue the Discussion:

Join the COVID-19 discussion groups for healthcare professionals on MedShr:

References:

[1] COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. [Accessed 12/10/20]

[2] Food and Drug Administration. Recommendations for Investigational COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma [Internet]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/investigational-new-drug-ind-or-device-exemption-ide-process-cber/recommendations-investigational-covid-19-convalescent-plasma [Accessed 12/10/20]

[3] Mayo Clinic. Expanded Access Program [Internet]. Available at: https://www.uscovidplasma.org/ [Accessed 12/10/20]

[4] Joyner MJ, Bruno KA, Klassen SA, Kunze KL, Johnson PW, Lesser ER, Wiggins CC, Senefeld JW, Klompas AM, Hodge DO, Shepherd JRA, Rea RF, Whelan ER, Clayburn AJ, Spiegel MR, Baker SE, Larson KF, Ripoll JG, Andersen KJ, Buras MR, Vogt MNP, Herasevich V, Dennis JJ, Regimbal RJ, Bauer PR, Blair JE, van Buskirk CM, Winters JL, Stubbs JR, van Helmond N, Butterfield BP, Sexton MA, Diaz Soto JC, Paneth NS, Verdun NC, Marks P, Casadevall A, Fairweather D, Carter RE, Wright RS. Safety Update: COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma in 20,000 Hospitalized Patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 Sep;95(9):1888-1897. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.028. Epub 2020 Jul 19. PMID: 32861333; PMCID: PMC7368917.

[5] Hayek S. Convalescent Plasma for Treatment of COVID-19 [Internet]. American College of Cardiology; 2020 Oct 5 [cited 2020 Oct 12].

[6] Estcourt LJ, Roberts DJ. Convalescent plasma for covid-19. BMJ. 2020 Sep 15;370:m3516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3516. PMID: 32933945.

[7] NHS Blood and Transplant. COVID-19 Research: Convalescent plasma trials [Internet]. Available at: https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/covid-19-research/research-and-trials/plasma-trials/ [Accessed 12/10/20]

[8] Database search at NIH Clinical Trials for search criteria: "Covid19 +convalescent plasma + randomized"

[9] National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project. Key Scientific Papers [Internet]. Available at: https://ccpp19.org/key-scientific-papers/index.html [Accessed 12/10/20]

[10] The Lancet Haematology. The resurgence of convalescent plasma therapy. Lancet Haematol. 2020 May;7(5):e353. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30117-4. PMID: 32359447; PMCID: PMC7190301.

[11] Roback JD, Guarner J. Convalescent Plasma to Treat COVID-19: Possibilities and Challenges. JAMA. 2020 Apr 28;323(16):1561-1562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4940. PMID: 32219429.

[12] Mucha SR, Quraishy N. Convalescent plasma for COVID-19. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020 Aug 5. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc056. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32759176.

[13] Bloch EM, Shoham S, Casadevall A, Sachais BS, Shaz B, Winters JL, van Buskirk C, Grossman BJ, Joyner M, Henderson JP, Pekosz A, Lau B, Wesolowski A, Katz L, Shan H, Auwaerter PG, Thomas D, Sullivan DJ, Paneth N, Gehrie E, Spitalnik S, Hod EA, Pollack L, Nicholson WT, Pirofski LA, Bailey JA, Tobian AA. Deployment of convalescent plasma for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020 Jun 1;130(6):2757-2765. doi: 10.1172/JCI138745. PMID: 32254064; PMCID: PMC7259988.

[14] Piechotta V, Chai KL, Valk SJ, Doree C, Monsef I, Wood EM, Lamikanra A, Kimber C, McQuilten Z, So-Osman C, Estcourt LJ, Skoetz N. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jul 10;7(7):CD013600. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub2. PMID: 32648959; PMCID: PMC7389743.

[15] Sewell HF, Agius RM, Kendrick D, Stewart M. Vaccines, convalescent plasma, and monoclonal antibodies for covid-19. BMJ. 2020 Jul 9;370:m2722. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2722. PMID: 32646867.

[16] Hansen J, Baum A, Pascal KE, Russo V, Giordano S, Wloga E, Fulton BO, Yan Y, Koon K, Patel K, Chung KM, Hermann A, Ullman E, Cruz J, Rafique A, Huang T, Fairhurst J, Libertiny C, Malbec M, Lee WY, Welsh R, Farr G, Pennington S, Deshpande D, Cheng J, Watty A, Bouffard P, Babb R, Levenkova N, Chen C, Zhang B, Romero Hernandez A, Saotome K, Zhou Y, Franklin M, Sivapalasingam S, Lye DC, Weston S, Logue J, Haupt R, Frieman M, Chen G, Olson W, Murphy AJ, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD, Kyratsous CA. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science. 2020 Aug 21;369(6506):1010-1014. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0827. Epub 2020 Jun 15. PMID: 32540901; PMCID: PMC7299284.

[17] Cohen J. Update: Here’s what is known about Trump’s COVID-19 treatment [Internet]. Science Magazine; 2020 [updated 2020 Oct 7; cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: doi:10.1126/science.abf0974

[18] Fischer JC, Zänker K, van Griensven M, Schneider M, Kindgen-Milles D, Knoefel WT, Lichtenberg A, Tamaskovics B, Djiepmo-Njanang FJ, Budach W, Corradini S, Ganswindt U, Häussinger D, Feldt T, Schelzig H, Bojar H, Peiper M, Bölke E, Haussmann J, Matuschek C. The role of passive immunization in the age of SARS-CoV-2: an update. Eur J Med Res. 2020 May 13;25(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s40001-020-00414-5. PMID: 32404189; PMCID: PMC7220618.

[19] Pau AK, Aberg J, Baker J, Belperio PS, Coopersmith C, Crew P, Glidden DV, Grund B, Gulick RM, Harrison C, Kim A, Lane HC, Masur H, Sheikh V, Singh K, Yazdany J, Tebas P. Convalescent Plasma for the Treatment of COVID-19: Perspectives of the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Sep 25. doi: 10.7326/M20-6448. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32976026.

[20] Mair-Jenkins J, Saavedra-Campos M, Baillie JK, Cleary P, Khaw FM, Lim WS, Makki S, Rooney KD, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Beck CR; Convalescent Plasma Study Group. The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2015 Jan 1;211(1):80-90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu396. Epub 2014 Jul 16. PMID: 25030060; PMCID: PMC4264590.

[21] Bloch EM, Shoham S, Casadevall A, Sachais BS, Shaz B, Winters JL, van Buskirk C, Grossman BJ, Joyner M, Henderson JP, Pekosz A, Lau B, Wesolowski A, Katz L, Shan H, Auwaerter PG, Thomas D, Sullivan DJ, Paneth N, Gehrie E, Spitalnik S, Hod EA, Pollack L, Nicholson WT, Pirofski LA, Bailey JA, Tobian AA. Deployment of convalescent plasma for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020 Jun 1;130(6):2757-2765. doi: 10.1172/JCI138745. PMID: 32254064; PMCID: PMC7259988.

[22] Murphy M, Estcourt L, Grant-Casey J, Dzik S. International Survey of Trials of Convalescent Plasma to Treat COVID-19 Infection. Transfus Med Rev. 2020 Jul;34(3):151-157. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2020.06.003. Epub 2020 Jun 27. PMID: 32703664; PMCID: PMC7320682.

[23] Focosi D, Anderson AO, Tang JW, Tuccori M. Convalescent Plasma Therapy for COVID-19: State of the Art. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020 Aug 12;33(4):e00072-20. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00072-20. PMID: 32792417; PMCID: PMC7430293.

[24] Bloch EM, Goel R, Wendel S, Burnouf T, Al-Riyami AZ, Ang AL, DeAngelis V, Dumont LJ, Land K, Lee CK, Oreh A, Patidar G, Spitalnik SL, Vermeulen M, Hindawi S, Van den Berg K, Tiberghien P, Vrielink H, Young P, Devine D, So-Osman C. Guidance for the procurement of COVID-19 convalescent plasma: differences between high- and low-middle-income countries. Vox Sang. 2020 Jun 13:10.1111/vox.12970. doi: 10.1111/vox.12970. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32533868; PMCID: PMC7323328.

[25] National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project. Component 3: Clinical Trials [Internet]. Available at: https://ccpp19.org/healthcare_providers/component_3/index.html [Accessed 12/10/20]

[26] Bloch EM, Goel R, Montemayor C, Cohn C, Tobian AAR. Promoting access to COVID-19 convalescent plasma in low- and middle-income countries. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020 Sep 20:102957. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102957. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32972861; PMCID: PMC7502258.

[27] Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020 Apr 1;130(4):1545-1548. doi: 10.1172/JCI138003. PMID: 32167489; PMCID: PMC7108922.

Article by Dr Ryan Broll, MedShr Open Editorial Team, Medical Education Fellow

Loading Author...

Sign in or Register to comment