Chagas Disease - Current Guidelines and Recommendations

What is Chagas Disease?

Chagas disease is a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Without adequate treatment, chagas infection will persist for a patient's lifetime with a significant burden of morbidity and mortality. This chronic infection can lead to severe gastric motility issues (such mega-oesophagus or megacolon) and approximately one third of patients with untreated chagas disease will progress to develop serious cardiac disease. This includes dilated cardiomyopathy with heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, conduction disturbances and thromboembolic events [1].

Between 6-8 million people are estimated to have chagas disease worldwide with the vast majority of infections confined to Mexico, Central America and South America - areas relatively lacking in infrastructure and funding for robust healthcare systems. However, due to increased population mobility seen as a result of increased globalisation, non-endemic countries such as Europe and the US are now also seeing more imported Chagas disease [1]. It is therefore important to spread awareness of Chagas disease beyond these endemic regions to ensure that all patients receive the best care.

How is it transmitted?

Triatomine insects, otherwise known as kissing bugs, carry the parasite T. cruzi which causes Chagas disease.These insects often live in the cracks and crevices of poorly built homes in rural or suburban areas. They normally hide during the day and become active at night, when they feed on blood and drop their faeces on the skin. The insect bites causes the person to scratch the faeces containing the parasite over the broken skin, and the parasite enters the bloodstream. The parasites can also be transmitted through the eyes or mouth [2].

Around 20% of T.cruzi cases are transmitted through blood transfusions or organ transplants. Vertical transmission from infected mother to their child makes up around 1% of cases, and a very small number of cases can be transmitted by accidental ingestion of food contaminated with T. cruzi [2].

Key Guidelines

These guidelines cover the following key areas which have been summarised below:

Screening

Investigation

Antiparasitic treatment

Long term management

Regional Guidelines:

Pan-American Health Organisation/World Health Organisation (PAHO/WHO):

Endemic country local guidelines:

Brazil:

Chile:

Buenos Aires:

Venezuela:

Non endemic country recommendations:

A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association:

Screening

There is no vaccine for Chagas disease. Therefore screening programmes are vital for diagnosis and early treatment of disease.

Recommendations

All individuals from endemic areas should be screened for Chagas Disease on at least one occasion [3]

In endemic regions, pregnant women as well as newborns from infected mothers should be tested [3]

Blood donors should always be tested [3]

Screening is recommended for all migrants and travellers with risk factors for T. cruzi infection [4]

See our 'How to Test for Chagas Disease' section below to find out more about testing.

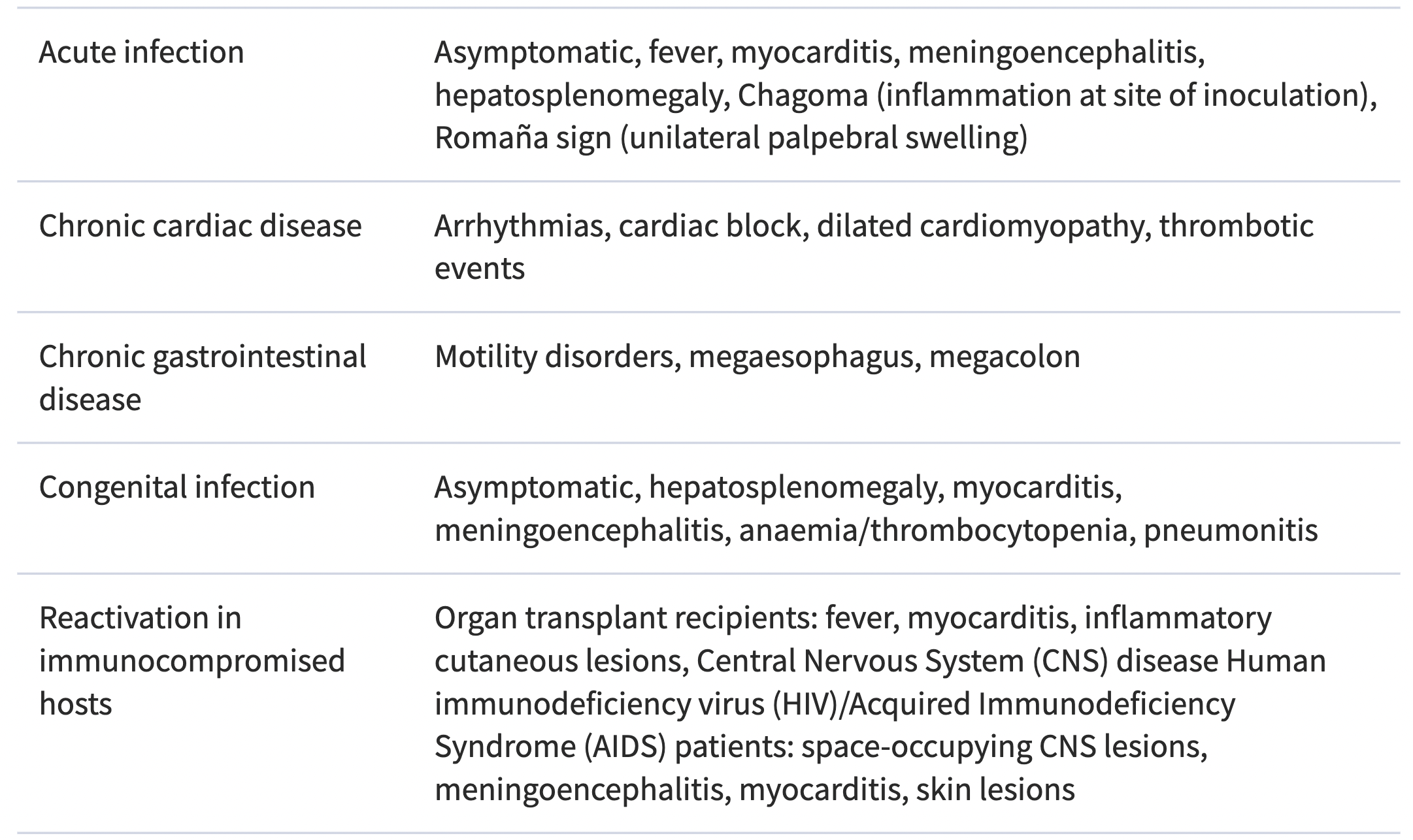

When to Suspect Chagas Disease

The table below is taken from the 2018 PAHO/WHO Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chagas Diseases. Such signs and symptoms in patients presenting in endemic regions or in regions with high migration from endemic countries should prompt Chagas Disease testing.

Main clinical manifestations of T. cruzi infection

How to Test for Chagas Disease

Diagnosis for acute and congenital phase of Chagas disease is obtained through Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or direct visualisation of the parasite in blood.

Chronic Chagas Disease is more difficult to test as parasite levels are often much lower. Therefore testing relies on the positivity of two serological tests which detect specific antibodies (enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA), Indirect Immunofluorescence or Indirect Hemagglutination) [5].

Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) for Chagas disease have been developed and are approved for use for screening purposes. There is ongoing and promising research to identify if two RDTs could be used instead of serological testing. This alternative would be beneficial to rural communities with little or no access to serological testing, increasing the chances of catching Chagas disease at an earlier stage and administering treatment sooner [5].

Antiparasitic Treatment

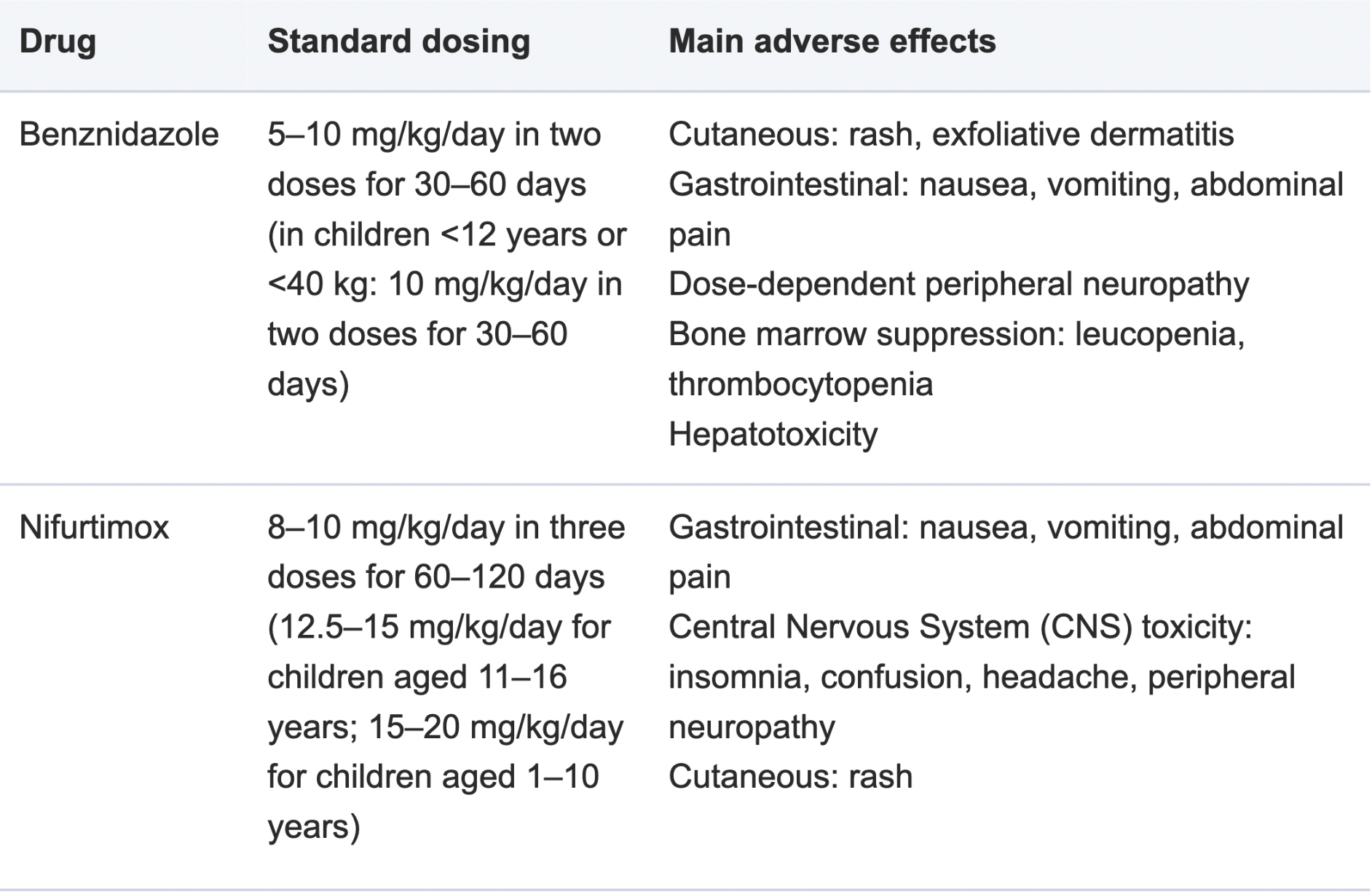

If treatment is started during the acute phase, both Benznidazole or Nifurtimox are effective agents in killing the parasite. All infected children must be treated (including children with chronic chagas disease) but Benznidazole and Nifurtimox should not be administered to pregnant women.

Antiparasitic drugs will be less effective the longer a person has been infected with Chagas Disease. For chronic chagas disease in adults (without specific organ damage), it is important to weigh the potential benefits of antiparasitic treatment in preventing or delaying the development of Chagas disease against possible adverse reactions (which affect up to 40% of treated patients), age and comorbidities [4].

Adults with Chronic Chagas Disease and specific organ damage are not recommended for antiparasitic treatment due to the lack of evidence that treatment has a significant impact on death or the progression of heart disease [4].

It is important to treat patients with Chagas disease for their associated pathologies whether this be medical or surgical, pathophysiological or symptomatic treatments [4].

The table below is taken from:

Chagas disease: comments on the 2018 PAHO Guidelines for diagnosis and management

Managing Chagas Disease

Once a diagnosis of Chagas Disease has been made it is important to carry out the following primary investigations:

Full history

Physical examination

An ECG

30-second rhythm strip

Chest X-ray

Echo (if available)

If this evaluation raises suspicion of more severe Chagas disease forms, then referral is recommended for cardiac and gastrointestinal workup [7].

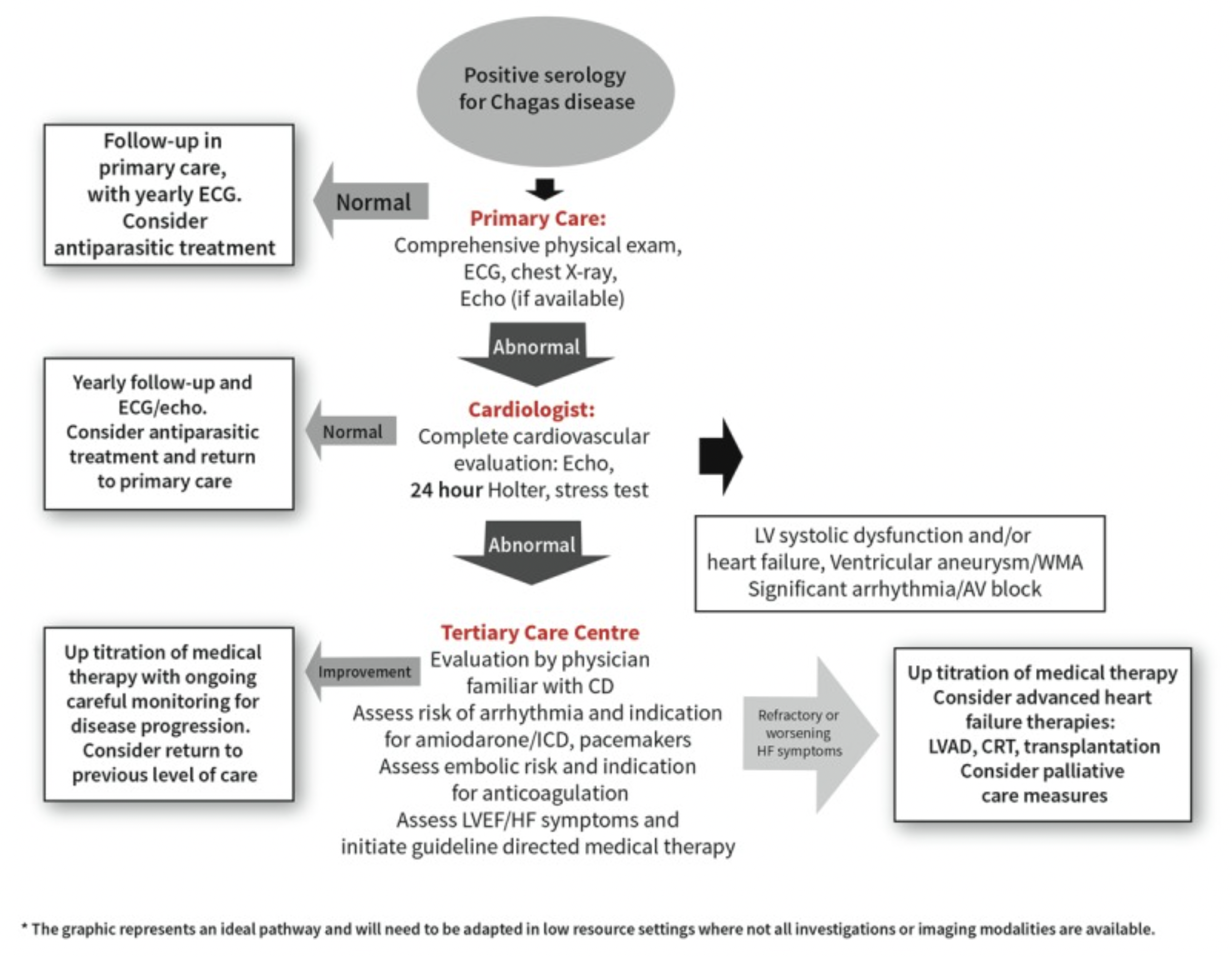

The following diagram from the WHF IASC Roadmap on Chagas Disease shows how patients should be monitored following Chagas disease diagnosis in low resource settings. Note yearly ECGs should be performed for patients with normal examination findings.

The following situations should prompt additional follow-up beyond the diagram above:

Worsening clinical status

Right sided HF as demonstrated by systemic congestion

occurrence of a thromboembolic event

Arrhythmic episode (new-onset AF, bradyarrhythmias or tachyarrhythmias that cause palpitations, syncope, and aborted sudden death)

The need for pacemaker or ICD device

We know that it can often be difficult to to detect or manage Chagas disease due to lack of resources in the rural areas in which it is endemic. At MedShr we are building a network of health care professionals interested in Chagas Disease to promote awareness and deliver education around the disease.

Join our Chagas Disease Global Education Network - through sharing your experiences of managing patients with Chagas Disease and your practical solutions to overcome barriers to detection and treatment, we believe this network will help to improve the lives of patients with Chagas Disease and ultimately save lives.

Loading Author...

Sign in or Register to comment