Sickle Cell Disease - A Public Health Model

Sickle Cell Disease is an inherited blood cell disorder which causes mutations in red blood cells. These mutations cause the blood cell to change shape from being round to becoming sickled (C shaped). Sickled cells don’t live as long as healthy red blood cells and can get stuck in blood vessels causing painful sickle cell crises which can lead to death. SCD is the most common life-threatening genetic disorder among people of African heritage and is also highly prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, the Mediterranean basin, and the Middle East. Each year, over 300,000 children are born with SCD, and many of them do not have access to adequate care to prevent painful crises and prolong their life. There are many low cost, effective preventive SCD interventions and therapies such as hydroxyurea have also seen massive reduction in cost. Here, we aim to highlight these interventions and provide our readers with the most up to date guidance and practices in SCD diagnosis and management.

A Tried and Tested Healthcare Package

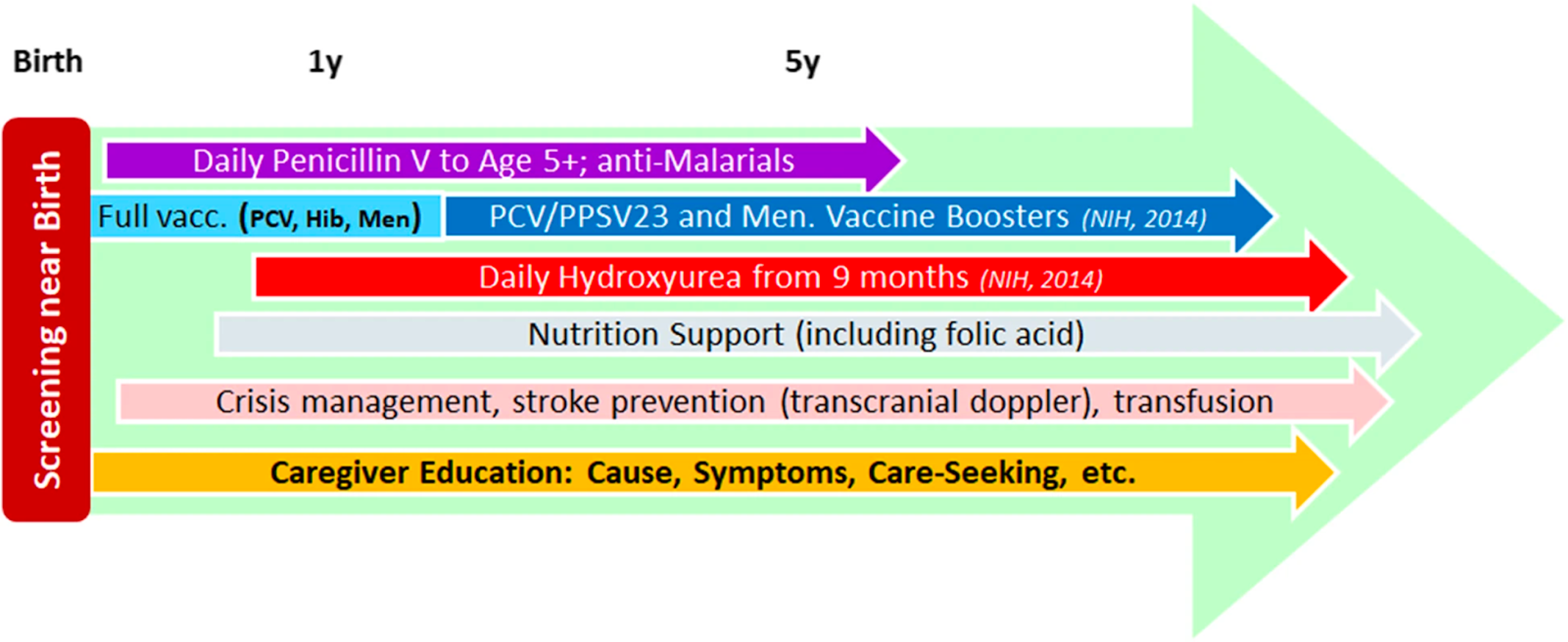

Adapted from: Caring for Africa’s sickle cell children: will we rise to the challenge? [1]

“The standard public-health care package for SCD children, developed in middle- and high-income countries over the past 50–60 years, consists of several elements:”

1. Screening in early infancy

Neonatal / early infancy screening is paramount, this allows for prompt identification of sickle cell disease and appropriate monitoring and management going forward.

2. Penicillin V prophylaxis

Sickle cell disease can cause damage to the spleen which normally makes antibodies to protect against encapsulated bacteria. Penicillin V protects children from such bacterial infections and giving prophylaxis during early childhood was the first preventive SCD intervention introduced in the West, with dramatic mortality reduction.

Some organizations now recommend continuing well beyond age 5 in high-burden, limited-resource areas. Penicillin V availability and price vary across Africa, but it has long been a WHO Essential Medicine, and its global reference price is a few US cents per daily dose. Therefore, both supply and cost can be stabilized. For penicillin allergic children, macrolides are indicated; they are also inexpensive and widely available.

3. Antimalarial Prophylaxis

Although carriers of the sickle gene (Hb genotype AS) are somewhat protected from malaria, SCD patients have an increased risk of death due to malarial infections. This may be due to anaemia, hyposplenism and a weakened immune system. Antimalarial prophylaxis is indicated, is widely available, and reduces the frequency of clinical episodes.

4. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) and Haemophilus influenza B (Hib) vaccine

Children affected with SCD are at high risk of infection from encapsulated bacteria, especially Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b. Both vaccines are both delivered during early infancy under the WHO Expanded Program on Immunisation and therefore affordable and widely available. Making vaccines and boosters available at older ages universally available and affordable might require SCD-specific support.

5. Management with Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea (HU) promotes HbF production, among other benefits, and has been demonstrated in the West to be highly effective in reducing mortality and morbidity, including anemia mitigation, among children and adults, and in improving long-term prognosis. Safety and efficacy in African children were demonstrated by several recent trials and observational studies. Hydroxyurea is also a WHO Essential Medicine; its availability is expanding, and prices are dropping.

Key publications and Guidance to Support this Public Care Package for SCD

This pilot study demonstrates how integration of newborn screening into existing primary health-care immunisation programmes is feasible and can rapidly be implemented with limited resources. Point-of-care tests are reliable and accurate in newborn screening for sickle cell disease [2]

This article looked at the best ways to address SCD in Africa and recommended approaches to partnerships and research opportunities in sub-Saharan Africa

"1. Involve local leaders as collaborators, especially from academia and government.

2. Create partnerships that emphasize training and local capacity building.

3. Conduct prospective research to ensure results are evidence-based.

4. Follow rigorous ethical and research standards, to protect the rights of potentially vulnerable study participants.

5. Train and use local personnel whenever possible, increasing in-country expertise and limiting exportation of samples and data.” [3]

Hydroxyurea for Children with Sickle Cell Anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa

This study demonstrates the safety and efficacy of hydroxyurea therapy in children with sickle cell disease. “Hydroxyurea treatment was feasible and safe in children with sickle cell anemia living in sub-Saharan Africa. Hydroxyurea use reduced the incidence of vaso-occlusive events, infections, malaria, transfusions, and death, which supports the need for wider access to treatment.” [4]

Guidelines from the American Society of hematology

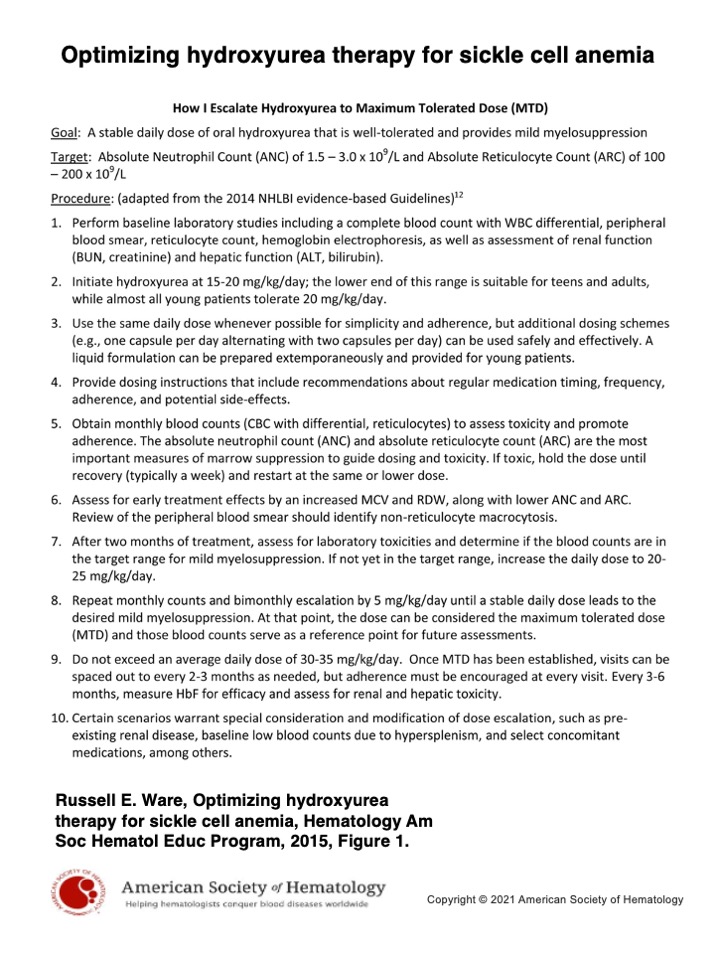

Optimizing hydroxyurea therapy for sickle cell anemia

From publication: [6]

This video outlines what the American Society of Hematology is doing to address the Global Burden of Sickle Cell Disease

MedShr's Sickle Cell Disease Global Network

The implementation of these initiatives in the nations with the highest prevalence of SCD will have an enormous impact on the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. At MedShr we are building a global network of healthcare professionals with an interest in SCD to improve understanding and knowledge of the disease and highlight the most up to date guidelines in practice.

Join our Sickle Cell Disease Global Education Network - through sharing your experiences of managing patients with Sickle Cell Disease and your practical solutions to overcome barriers to screening, diagnosis and treatment, we believe this network will help to improve the lives of patients with Sickle Cell Disease and ultimately save lives.

Author: Dr Asif Qasim

References

[1] Oron, Assaf P., et al. "Caring for Africa’s sickle cell children: will we rise to the challenge?." BMC medicine 18.1 (2020): 1-8.

[2] Nnodu, Obiageli E., et al. "Implementing newborn screening for sickle cell disease as part of immunisation programmes in Nigeria: a feasibility study." The Lancet Haematology 7.7 (2020): e534-e540.

[3] McGann, Patrick T., Arielle G. Hernandez, and Russell E. Ware. "Sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa: advancing the clinical paradigm through partnerships and research." Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 129.2 (2017): 155-161.

[4] Tshilolo, Léon, et al. "Hydroxyurea for children with sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa." New England Journal of Medicine 380.2 (2019): 121-131.

[5] DeBaun, M. R., et al. "American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrovascular disease in children and adults." Blood advances 4.8 (2020): 1554-1588.

[6] Ware, Russell E. "Optimizing hydroxyurea therapy for sickle cell anemia." Hematology 2014, the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book 2015.1 (2015): 436-443.

Loading Author...

Sign in or Register to comment